This article is authored by Sterling Sackey and was originally published on Autoblog in September 2016.

The original NSX, introduced in production form in 1990 by Honda and to the United States market under the Acura brand in 1991, is now officially 25 plus years old. Generations of car enthusiasts grew to love the original NSX over the 15 years it was in production and beyond, but as an fan and owner, I think it’s important to fully realize just how monumental a shift the introduction of the NSX was in the art of making cars. So, retold 25 years later, this is the abridged story of the NSX, Honda’s supercar.

The Idea

The NSX was an extremely risky project for Honda, a company that in the late 1980’s was nowhere near the corporate juggernaut that it is today. Honda’s eponymous founder, Soichiro Honda, was still involved in decision-making at the company during this time under the role of “Supreme Advisor,” and it is debatable whether the NSX project in its infancy would have gone forward at all had he not still been pushing the company towards the spirit of technical achievement it had been known for in the prior decades. Mr. Honda was still so involved during this period, in fact, that when the first batch of 300 production NSXs were made with a version of the Acura badge he didn’t like, he ordered all of the cars stopped at port in the USA, the new badges applied, and the offending incorrect badges sent back to Japan to be systematically destroyed. This was clearly a man who paid attention to the details, but I digress.

Honda as a company devoted $140 million dollars to the NSX project ($250 million in today’s money), half of which would go to developing the car, and the remainder of which would go to building a new state-of-the-art factory to assemble it. Honda’s own goals for the NSX were actually exactly as most media stories portray the car today: to build a bona-fide exotic supercar, but one without the ergonomic and reliability penalties associated with that type of car. They didn’t want to sacrifice the needs of the driver to the supposed demands of performance, demands that they felt didn’t have to be there in making a truly top-level performance machine. The R&D team wanted a car that could hang with heavyweight exotics in a straight line, play with smaller and more lightweight sports cars in the curves, and cruise in serenity on the freeway. Essentially, they wanted it all, and the brief was to have a car that could do everything without compromise.

Said goal was not just wishful thinking at the time, it was actually considered impossible – at any price. There was no way in hell anyone could make a car lightweight, comfortable, ergonomic, quiet, loud, sporty, aggressive, and powerful all at the same time. Contemporary exotic cars – the Ferrari 328 & 348, Lotus Esprits, Porsche 911s, and Chevrolet Corvettes – all had huge compromises in various departments, and that’s just the way a supercar had to be. These quirks were part of the so-called exotic car experience, and drivers & reviewers welcomed them because they couldn’t imagine it being any other way. Plus, the idea of Honda making a supercar? Everyone (including the competition) laughed when they heard the notion. Honda didn’t make supercars, they made cheap economy hatchbacks and scooters. It simply wouldn’t happen, or so they thought.

Development & Technology

It was decided fairly early on in the development process that if the NSX were to compete with the highest-level offerings from the European greats, it had to be a mid-engined design. And so it was, the final car boasting a McLaren-Honda MP4/4-inspired 42% front / 58% rear weight distribution. The engineers were careful to position the fuel tank and seats so that the weight distribution remained almost identical with or without passengers, and with or without a full load of fuel. The mid-engine also allowed for a low cowl-height up front, where 15-inch wheels were used as opposed to the 16-inchers in the rear to further lower the hood-line and avoid impeding into the passenger compartment’s foot and leg room. Honda engineers felt that one of the biggest ergonomic issues with the competitors was their disregard for taller drivers and often annoyingly offset pedal boxes, something the NSX avoided nicely due to a steadfast focus on packaging (they even managed to squeeze in a dead pedal!).

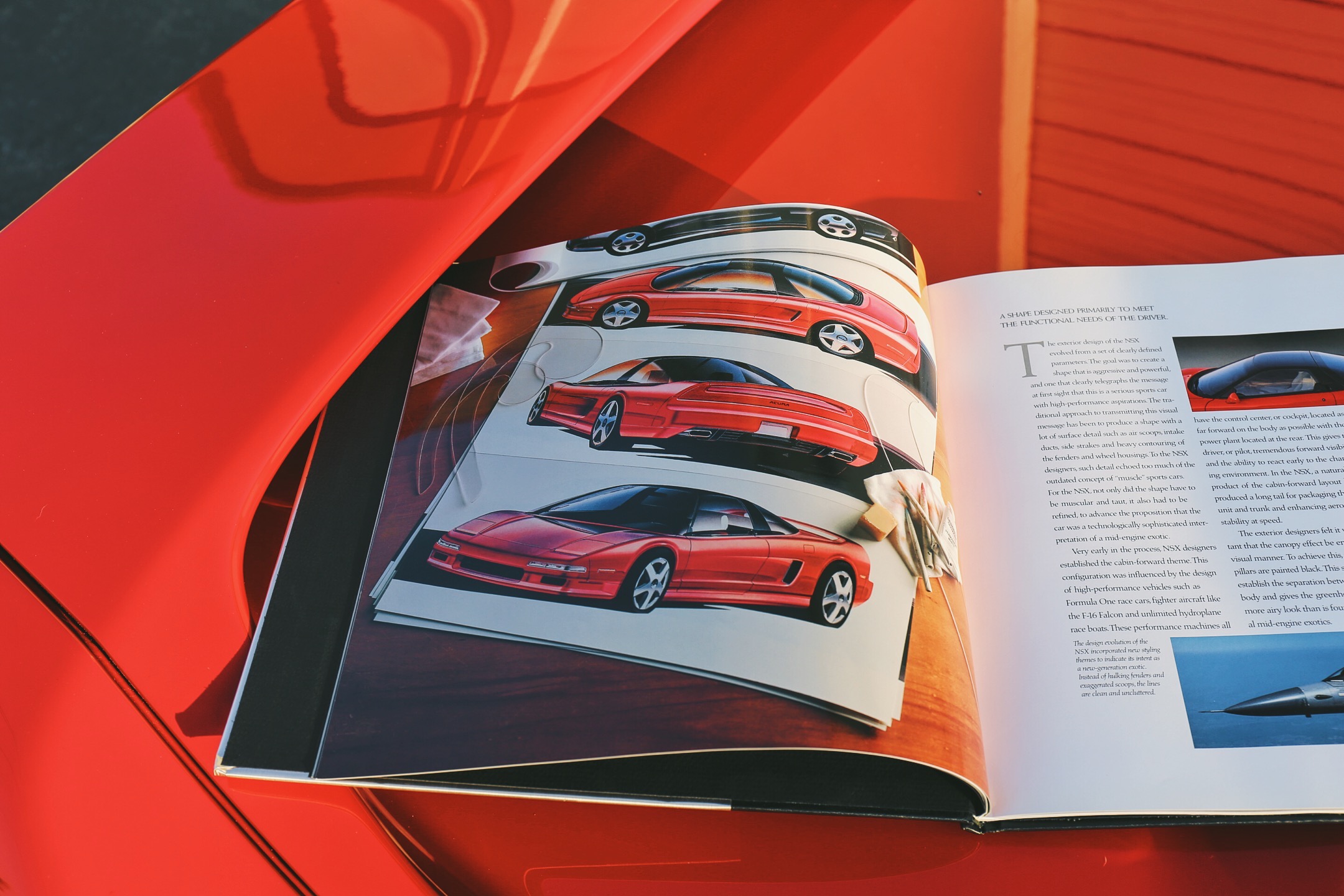

The NSX’s mid-engine platform also contributed a great deal to its exterior’s visual design. The car’s overall styling was intended to be “refined” like the rest of the vehicle, avoiding the trivialities and trends of its rivals; there were to be no side-strakes, air scoops, and huge fender flares here. The functional needs of the driver were paramount to the NSX ethos, so it was decided that a greenhouse-like canopy would provide the best visibility possible. A cabin-forward look was also established early, not only a semi-necessity with the mid-engined platform, but a decision taking design inspiration from F1 cars, the F-16 Falcon fighter aircraft, and, less commonly noted, unlimited hydroplane racing boats. Again, this cab-forward design was intended to give the driver tremendous visibility and the ability to react early to the environment around him. However, it also helped package the full-size trunk behind the engine, an element added partly for practicality and partly for the high-speed stability the team found that a long tail provided. The canopy effect the engineers had developed was visually distinguished by the black-painted roofs of early NSXs, giving the effect of a completely separate unit to the rest of the body.

When it came to chassis development, the NSX would have to be both light and rigid to meet its R&D goals. Lightness was important for obvious reasons, and rigidity was prioritized for both dynamic responsiveness and driving refinement (a more rigid chassis will cause less noise, vibration, and harshness after all). The team experimented with high-strength steels and even carbon fiber, but in the end it was decided that the car would be constructed entirely from aluminum. When the Honda research team initially reached out to aluminum suppliers, the suppliers didn’t take them seriously in the slightest; “You want to build the chassis out of what?” Aluminum had simply never been used for an entire monocoque chassis, and it was going to be a huge struggle to make it work; suppliers assumed Honda would give up and balk on any contracts. In the end, though, through the use of various extruding methods, different types of aluminum selected for different areas, and a Cray II supercomputer for modeling and stress analyses, the first all-aluminum spaceframe chassis used in a production car was born. The chassis eventually became even more rigid than the initial goals, the result of a certain test driver by the name of Ayrton Senna driving an early test car and telling the team it felt, quote, “fragile.” They went back to the drawing board, and the production chassis became 50% stiffer still. The final version weighed in at 452 lbs, 40% lighter than a steel chassis but significantly stronger.

Aerodynamics were not a critical focus of the NSX project so much as the importance of packaging and ease of use (visibility, ergonomics, etc.), but the team did have some goals in mind in this department. While the .32 coefficient of drag was respectable for its day, ensuring the car had zero lift was considered a necessity. The shape, low in the front and rising gradually to the back, aided in high-speed stability. The long tail and integrated rear spoiler helped especially in this effort, the latter maintaining laminar airflow and reducing turbulence as it left the rear of the car. The large side air intakes were used for feeding the engine’s induction system on the left side (driver’s side on left-hand drive cars), which helped to create a ram air effect, and for cooling the alternator on the right side.

While aero was not a critical point of the NSX’s engineering process, the suspension and overall handling setup, with absolute certainty, was. The goal for the NSX suspension system was to out-handle contemporary exotic cars while maintaining a more user-friendly nature than those same competitors. Honda wanted the car to be the driver’s ally rather than his or her enemy, to amplify driving talents rather than diminish them. These goals called for double-wishbone suspension all-around, providing ideal suspension geometry that wouldn’t be unpredictable as a result of bumps or body motions. A unique “compliance pivot” system was developed for the front suspension to help keep front toe change to near-zero throughout the suspension’s range of travel. Almost all of the suspension’s components were made from forged aluminum. The wheels, even, were forged and spun from solid aluminum billet (yes, those unassuming looking 15/16 inchers!). Yokohama, in partnership with Honda for developing the NSX tires, went through 10 molds, 100 tire specifications, and 6,000 tires total during the R&D process. Only then was it determined that a tire good enough to grace the NSX was ready. Steering was unassisted for increased road feel, and four-wheel steering was considered but axed due to the 100-pound weight penalty it would add. Braking was assisted by a 4-channel ABS that controlled each wheel individually using a 16-bit microprocessor, an incredible system for its day. To tie it all off in the handling department, towards the end of development the previously mentioned McLaren-Honda F1 champion Ayrton Senna and Indy champion Bobby Rahal signed off on final suspension calibrations for good measure.

The NSX’s engine is perhaps its most underappreciated asset, and one that engineers toiled over much more than is realized. Multiple powerplants were considered for the NSX project: a V6, a V6 twin-turbo, and a V8. It was ultimately determined that the turbo engine would lack the throttle response desired for the car, and the V8 would be too heavy to maintain the lightweight goals in mind, so both were scrapped in favor of a naturally-aspirated V6. However, this aluminum engine dubbed the C30A was not in any way, shape, or form a run-of-the-mill V6 out of an Accord or Legend modified for more power, as is often the myth. The design was clean-sheet, and used groundbreaking technology to achieve a then-amazing 90 horsepower per liter, beating the Ferrari 328’s V8 for both outright power and power-per-liter, and just slightly bested on both fronts by the subsequent Ferrari 348. Engineers employed the first-ever use of titanium connecting rods in a production car engine in the C30A, reducing weight by 30% and upping the redline from a theoretical 7,300 RPM to a full 8,000 RPM. The new Variable Volume Induction System, or VVIS, opened a second intake plenum chamber at 4,800 RPM to aid induction volume into each cylinder. The pièce de résistance was Honda’s VTEC system, which had never been seen before in a USA-marketed Honda or Acura product. This system gave the engine the combination of high-end power and low-end tractability that the Honda engineers wanted in their everyday supercar. VTEC allowed essentially for two cam profiles, so that high end breathing could be improved without a lumpy engine around town. The proof was in the numbers: Without VTEC, prototype engines hit a maximum of 250 horsepower. With VTEC, the production engine debuted at 270.

The rest of the NSX’s powertrain matched the engine for forward thinking. An all-wheel drive system was considered, but ditched in favor of rear wheel drive due to weight, as it was determined the system would add 200 pounds. A 5-speed manual was employed (4-speed automatic optional, and sacrilegious), with extra attention paid to a solid and engaging short-throw shifter feel. A “torque control differential,” with a planetary gearset and wet clutch to limit inside wheelspin, helped maintain stability at speed and traction on slippery surfaces. The car had one of the first advanced traction control systems (defeatable, of course), which would help maintain control and determine road conditions using individual wheel speed, steering angle, yaw rate, and even an onboard vibration sensor (should the NSX driver find himself on a bumpy dirt road).

Production & Press

Honda’s $70-million dollar (estimated) Tochigi plant, built specially for production of the NSX, employed 200 elite workers selected from other Honda factories for the privilege of building its new benchmark halo car. Any notion that the NSX, as the result of being a Honda, was a car built by robots, is incorrect. NSX chassis were mounted on dollies and moved by hand from station to station, ensuring each task was done with millimetric precision. Even portions of the chassis itself were bead-welded by hand. Workers at each station could take as long as they needed to precisely do their appointed job in assembling the car. At the end of the assembly line, each and every car was finalized by way of a full inspection and a 7.5-mile test drive on Tochigi’s banked oval circuit.

Top-brass at Honda stated publicly that they would consider the car a success if it broke even money-wise, as their main goals for the project were to showcase what the company was capable of and bring customers for their more “normal” cars into the showroom. It’s somewhat unlikely that the project did break even, as Honda only met its goal of 6,000 units per year in 1991, with sales trailing off majorly thereafter. Regardless, the car generated some amazing press for the company. Automobile in 1990 wrote, “…almost certainly the best car of its type ever made.” Motor Trend in the same year went further, saying, “[It’s]…the best sports car the world has ever produced. Any time. Any place. Any price.” They went on to note, “We’ve spent over 100 years developing the automobile. The NSX has made it worth the wait.” A job well done, then.

Driving the NSX Today

I’ve owned a Honda S2000 since 2009, and in past years I’ve always admired the NSX from afar, studying, but never owning. I finally got the chance to own not one but two NSXs this year following the opening of my business SW2 Heritage Cars, specializing in trading cars like these. While my first NSX was a later targa model, the red 1991 coupe pictured here is the car that really captured my heart and reminded me what a special machine the NSX really is. Driving the NSX is to understand just how serious Honda was when they set out to build a quote-unquote everyday supercar. After some time behind the wheel, it becomes very clear they weren’t joking; about either the everyday part or the supercar part. I’ve never in my automotive life come across a car that is so well suited for dual-purpose use, that is so well-behaved while brimming with passion at the same time. So, I thought I’d share the driving experience from my perspective.

Upon walking up to the NSX, it becomes clear this is a very low car. Park it next to a modern SUV, or sedan even, and either will tower over it. Open the long door and get into the driver’s seat, however, and the impression is surprisingly of sitting high up. This effect is both due to Honda’s propensity for installing their seats just an inch or two too high (the S2000 suffers from the same problem), but also because the NSX’s dash (or cowl-height, more properly) is so incredibly low. This has the effect of unbelievable sightlines out of the front window, the road just feet in front of the car only obstructed by the (absolutely 90’s, absolutely fantastic) pop-up headlights when driving at night. One feels as if they could reach out the windshield and palm the tarmac, the sightlines in this car are so good.

Time for a drive. Twist the traditional key, and the engine fires to life behind you with nary a sound. The only sense that this is something special is a slight side-to-side rumbling oscillation inherent to the low-profile 90-degree V6 design. At low RPMs and throttle openings, that V6 and the car overall are almost too refined, too quiet and subdued. This sense may lead the NSX uninitiated to disappointment – I thought this was supposed to be a sports car? Aside from the heavy unassisted steering, which lightens up above parking lot speeds, a driver who isn’t paying attention may mistake the NSX cruising experience for that of a contemporary Lexus LS400 (or Acura Legend, more appropriately). The clutch is light, the gears are long, and the transmission’s throw is easy. Wind noise and tire roar are very low at speed, and ride quality in town or on the highway are excellent, genuinely modern luxury car smooth (although maybe not quite as floaty as the aforementioned 90’s-era luxoboats). The A/C works perfectly even on 100 degree-plus days, and the excellent Bose stereo is a button-touch and antenna-raise away. The seats are almost lounge-chair good; no, actually the seats are better than any lounge-chair I’ve sat in. I quickly decided after experiencing them that I must source an example off eBay for a custom office chair, they’re that good… The engine, which has only a 210 lb/ft torque rating, is actually extremely gutsy around town, and in actuality feels like it has 100 lb/ft more than that number, certainly atypical for a 90’s Honda powerplant. Bumps along the road emit zero rattles or squeaks, owing to the rigid aluminum structure (later targas, unfortunately, are not quite so stiff). The exhaust is extremely quiet, perhaps more so than many modern “normal” cars. The wheel tilts and telescopes, and any frame up to the low 6-foot range could fit without much issue. So, in summary, the car is essentially a “pussycat” when cruising, really. It’s ergonomic, it’s quiet, it’s refined, and it’s even somewhat practical (A real trunk! In a supercar!). But everything changes when the driver starts to push harder.

Just when a driver thinks that his new NSX is too refined, too quiet, he’ll likely make the happy mistake of pulling out for a left-lane pass on some local roads. Dip into the throttle, and that V6, gulping air into its cylinders via the huge intake duct just outside your window, begins to emit one of the most glorious induction howls in modern motoring. The best way to describe the induction noise an NSX creates as it climbs through the revs is “half a V12, but better.” I am convinced there is no V6 that has ever sounded this good (truth be told, many of them actually don’t sound great at all), and while it is not overtly loud, Honda had to have had a musical instruments manufacturer in on this one, a-la Yamaha’s tie-in with the Lexus LFA. It’s that good. I get endless joy out of cruising down the 405 freeway in 5th gear, dropping it to 4th, flooring it for a few seconds to hear the symphony, returning to 5th, and repeating. The long gearing just helps the cause, because the sounds in each gear are prolonged before a shift is necessary. That gearing and the engine’s power level also mean that the car is not exceptionally fast, and by modern standards is more towards the bottom of the “quick” category. First gear ends at 45 MPH, and second ends at 81 MPH, hardly rally-car ratios like the later S2000. When one does have to shift, though, the throws are short and the horizontal spacing between gears is extremely tight, so it’s important to be careful not to get the wrong gear. The car’s unassisted steering is also light at speed when making corrections, but loads up under hard cornering significantly. This loading allows the driver to feel what the front suspension is doing; under compression, the steering gets heavier, and under rebound, lighter. Few cars, especially today, have this sort of communication between driver and front wheels. The suspension itself doesn’t feel soft under hard cornering, owing to the relatively low weight of the car (approx. 3,000 lbs even). Rather, it soaks up mid-corner bumps well while maintaining composure due to the inherently good geometry and spring travel that the double-wishbone setup affords. The brakes are not as good as in modern cars, but afford stopping power commensurate with the engine’s output, and I’ve never had a problem with them on a backroad. Overall, rest assured that the NSX is as much a joy in sport driving as it is in refined driving, and will satisfy fans of both camps to the same level.

In exploring the dual nature of the NSX, I’ve come to realize why so many of these cars have racked up the miles over the years. It is not uncommon to find NSX’s on the used market with over 200,000 miles, and 100,000 miles seems like a walk in the park for the platform. This doesn’t just have to do with Honda reliability, though. Instead, I think it has to do with the fact that this is a car that begs for the open road, a willing companion that entertains when the time is right and knows when the party is over. Driving an NSX over a large number of miles can be done in complete solitude and serenity, or in complete performance driving nirvana. It is just as home on Route 66 as it is on your favorite canyon twisties, owing to the engineers who put their hearts and souls into the NSX project to achieve just that goal. As a whole, the NSX is a true bona-fide supercar, and truly usable, all at the same time. And for that, I absolutely love it.